Copyright

Linux is a trademark of Linus Torvalds RedHat is a trademark of RedHat Software Inc.

Windows and DOS are trademarks of Microsoft Corp.

Sound Blaster is a trademark of Creative Labs

PostScript is a trademark of Adobe

File System Structure

- Why Share a Common Structure?

- Overview of File System Hierarchy Standard (FHS)

-

- FHS Organization

- Special File Locations Under Community Enterprise Linux

The ext3 File System

The default file system is the journaling ext3 file system.

Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID)

The basic idea behind RAID is to combine multiple small, inexpensive disk drives into an array to accomplish performance or redundancy goals not attainable with one large and expensive drive. This array of drives appears to the computer as a single logical storage unit or drive.

Swap Space

Managing Disk Storage

Implementing Disk Quotas

Disk space can be restricted by implementing disk quotas which alert a system administrator before a user consumes too much disk space or a partition becomes full.

Disk quotas can be configured for individual users as well as user groups. This makes it possible to manage the space allocated for user-specific files (such as email) separately from the space allocated to the projects a user works on (assuming the projects are given their own groups).

In addition, quotas can be set not just to control the number of disk blocks consumed but to control the number of inodes (data structures that contain information about files in UNIX file systems). Because inodes are used to contain file-related information, this allows control over the number of files that can be created.

The quota RPM must be installed to implement disk quotas.

Note

For more information on installing RPM packages, refer to Part II, "Package Management".

Access Control Lists

Files and directories have permission sets for the owner of the file, the group associated with the file, and all other users for the system. However, these permission sets have limitations. For example, different permissions cannot be configured for different users. Thus, Access Control Lists (ACLs) were implemented.

The Community Enterprise Operating System kernel provides ACL support for the ext3 file system and NFS-exported file systems. ACLs are also recognized on ext3 file systems accessed via Samba.

Along with support in the kernel, the acl package is required to implement ACLs. It contains the utilities used to add, modify, remove, and retrieve ACL information.

The cp and mv commands copy or move any ACLs associated with files and directories.

LVM (Logical Volume Manager)

Package Management with RPM

The RPM Package Manager (RPM) is an open packaging system, which runs on Community Enterprise Linux as well as other Linux and UNIX systems. CentOS, Inc. encourages other vendors to use RPM for their own products. RPM is distributed under the terms of the GPL.

The utility works only with packages built for processing by the rpm package. For the end user, RPM makes system updates easy. Installing, uninstalling, and upgrading RPM packages can be accomplished with short commands. RPM maintains a database of installed packages and their files, so you can invoke powerful queries and verifications on your system. If you prefer a graphical interface, you can use the Package Management Tool to perform many RPM commands. Refer to Chapter 12, Package Management Tool for details.

Important

When installing a package, please ensure it is compatible with your operating system and architecture. This can usually be determined by checking the package name.

During upgrades, RPM handles configuration files carefully, so that you never lose your customizations - something that you cannot accomplish with regular .tar.gz files.

For the developer, RPM allows you to take software source code and package it into source and binary packages for end users. This process is quite simple and is driven from a single file and optional patches that you create. This clear delineation between pristine sources and your patches along with build instructions eases the maintenance of the package as new versions of the software are released.

Note

Because RPM makes changes to your system, you must be logged in as root to install, remove, or upgrade an RPM package.

YUM (Yellowdog Updater Modified)

Yellowdog Update, Modified (YUM) is a package manager that was developed by Duke University to improve the installation of RPMs. yum searches numerous repositories for packages and their dependencies so they may be installed together in an effort to alleviate dependency issues. Community Enterprise Operating System.8 uses yum to fetch packages and install RPMs.

up2date is now deprecated in favor of yum (Yellowdog Updater Modified). The entire stack of tools which installs and updates software in Community Enterprise Operating System.8 is now based on yum. This includes everything, from the initial installation via Anaconda to host software management tools like pirut.

yum also allows system administrators to configure a local (i.e. available over a local network) repository to supplement packages provided by CentOS. This is useful for user groups that use applications and packages that are not officially supported by CentOS.

Aside from being able to supplement available packages for local users, using a local yum repository also saves bandwidth for the entire network. Further, clients that use local yum repositories do not need to be registered individually to install or update the latest packages from CentOS Network.

Product Subscriptions and Entitlements

- An Overview of Managing Subscriptions and Content

- Using CentOS Subscription Manager Tools

- Managing Special Deployment Scenarios

- Registering, Unregistering, and Reregistering a System

- Migrating Systems from RHN Classic to Certificate-based CentOS Network

- Handling Subscriptions

- Redeeming Subscriptions on a Machine

- Viewing Available and Used Subscriptions

- Working with Subscription yum Repos

- Responding to Subscription Notifications

- Healing Subscriptions

- Responding to Subscription Notifications

- Working with Subscription Asset Manager

- Updating Entitlements Certificates

- Configuring the Subscription Service

-

- CentOS Subscription Manager Configuration Files

- Using the config Command

- Using an HTTP Proxy

- Changing the Subscription Server

- Configuring CentOS Subscription Manager to Use a Local Content Provider

- Managing Secure Connections to the Subscription Server

- Starting and Stopping the Subscription Service

- Checking Logs

- Showing and Hiding Incompatible Subscriptions

- Checking and Adding System Facts

- Regenerating Identity Certificates

- Getting the System UUID

- Viewing Package Profiles

- Retrieving the Consumer ID, Registration Tokens, and Other Information

- Using the config Command

- CentOS Subscription Manager Configuration Files

- About Certificates and Managing Entitlements

Effective asset management requires a mechanism to handle the software inventory - both the type of products and the number of systems that the software is installed on. The subscription service provides that mechanism and gives transparency into both global allocations of subscriptions for an entire organization and the specific subscriptions assigned to a single system.

CentOS Subscription Manager works with yum to unit content delivery with subscription management. The Subscription Manager handles only the subscription-system associations. yum or other package management tools handle the actual content delivery. Chapter 13, YUM (Yellowdog Updater Modified) describes how to use yum.

This chapter provides an overview of subscription management in Community Enterprise Linux and the CentOS Subscription Manager tools which are available.

Network Interfaces

Under Community Enterprise Linux, all network communications occur between configured software interfaces and physical networking devices connected to the system.

The configuration files for network interfaces are located in the /etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/ directory. The scripts used to activate and deactivate these network interfaces are also located here. Although the number and type of interface files can differ from system to system, there are three categories of files that exist in this directory:

- Interface configuration files

- Interface control scripts

- Network function files

The files in each of these categories work together to enable various network devices.

This chapter explores the relationship between these files and how they are used.

Network Configuration

- Overview

- Establishing an Ethernet Connection

- Establishing an ISDN Connection

- Establishing a Modem Connection

- Establishing an xDSL Connection

- Establishing a Token Ring Connection

- Establishing a Wireless Connection

- Managing DNS Settings

- Managing Hosts

- Working with Profiles

- Device Aliases

- Saving and Restoring the Network Configuration

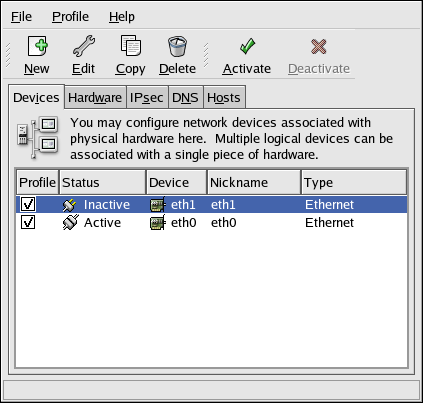

- Establishing an Ethernet Connection

To communicate with each other, computers must have a network connection. This is accomplished by having the operating system recognize an interface card (such as Ethernet, ISDN modem, or token ring) and configuring the interface to connect to the network.

The Network Administration Tool can be used to configure the following types of network interfaces:

- Ethernet

- Overview

- ISDN

- modem

- xDSL

- token ring

- CIPE

- wireless devices

It can also be used to configure IPsec connections, manage DNS settings, and manage the /etc/hosts file used to store additional hostnames and IP address combinations.

To use the Network Administration Tool, you must have root privileges. To start the application, go to the Applications (the main menu on the panel) > > , or type the command system-config-network at a shell prompt (for example, in an XTerm or a GNOME terminal). If you type the command, the graphical version is displayed if X is running; otherwise, the text-based version is displayed.

To use the command line version, execute the command system-config-network-cmd --help as root to view all of the options.

Main Window

Figure 16.1. Network Administration Tool

Tip

Use the CentOS Hardware Compatibility List (http://hardware.redhat.com/hcl/) to determine if Community Enterprise Linux supports your hardware device.

Controlling Access to Services

Maintaining security on your system is extremely important, and one approach for this task is to manage access to system services carefully. Your system may need to provide open access to particular services (for example, httpd if you are running a Web server). However, if you do not need to provide a service, you should turn it off to minimize your exposure to possible bug exploits.

There are several different methods for managing access to system services. Choose which method of management to use based on the service, your system's configuration, and your level of Linux expertise.

The easiest way to deny access to a service is to turn it off. Both the services managed by xinetd and the services in the /etc/rc.d/init.d hierarchy (also known as SysV services) can be configured to start or stop using three different applications:

- Services Configuration Tool

-

This is a graphical application that displays a description of each service, displays whether each service is started at boot time (for runlevels 3, 4, and 5), and allows services to be started, stopped, and restarted.

- ntsysv

-

This is a text-based application that allows you to configure which services are started at boot time for each runlevel. Non-

xinetdservices can not be started, stopped, or restarted using this program. chkconfig-

This is a command line utility that allows you to turn services on and off for the different runlevels. Non-

xinetdservices can not be started, stopped, or restarted using this utility.

You may find that these tools are easier to use than the alternatives - editing the numerous symbolic links located in the directories below /etc/rc.d by hand or editing the xinetd configuration files in /etc/xinetd.d.

Another way to manage access to system services is by using iptables to configure an IP firewall. If you are a new Linux user, note that iptables may not be the best solution for you. Setting up iptables can be complicated, and is best tackled by experienced Linux system administrators.

On the other hand, the benefit of using iptables is flexibility. For example, if you need a customized solution which provides certain hosts access to certain services, iptables can provide it for you. Refer to Section 46.8.1, "Netfilter and IPTables" and Section 46.8.3, "Using IPTables" for more information about iptables.

Alternatively, if you are looking for a utility to set general access rules for your home machine, and/or if you are new to Linux, try the Security Level Configuration Tool (system-config-securitylevel), which allows you to select the security level for your system, similar to the Firewall Configuration screen in the installation program.

Refer to Section 46.8, "Firewalls" for more information.

Important

When you allow access for new services, always remember that both the firewall and SELinux need to be configured as well. One of the most common mistakes committed when configuring a new service is neglecting to implement the necessary firewall configuration and SELinux policies to allow access for it. Refer to Section 46.8.2, "Basic Firewall Configuration" for more information.

Berkeley Internet Name Domain (BIND)

On most modern networks, including the Internet, users locate other computers by name. This frees users from the daunting task of remembering the numerical network address of network resources. The most effective way to configure a network to allow such name-based connections is to set up a Domain Name Service (DNS) or a nameserver, which resolves hostnames on the network to numerical addresses and vice versa.

This chapter reviews the nameserver included in Community Enterprise Linux and the Berkeley Internet Name Domain (BIND) DNS server, with an emphasis on the structure of its configuration files and how it may be administered both locally and remotely.

Note

BIND is also known as the service named in Community Enterprise Linux. You can manage it via the Services Configuration Tool (system-config-service).

OpenSSH

SSH™ (or Secure SHell) is a protocol which facilitates secure communications between two systems using a client/server architecture and allows users to log into server host systems remotely. Unlike other remote communication protocols, such as FTP or Telnet, SSH encrypts the login session, rendering the connection difficult for intruders to collect unencrypted passwords.

SSH is designed to replace older, less secure terminal applications used to log into remote hosts, such as telnet or rsh. A related program called scp replaces older programs designed to copy files between hosts, such as rcp. Because these older applications do not encrypt passwords transmitted between the client and the server, avoid them whenever possible. Using secure methods to log into remote systems decreases the risks for both the client system and the remote host.

Network File System (NFS)

A Network File System (NFS) allows remote hosts to mount file systems over a network and interact with those file systems as though they are mounted locally. This enables system administrators to consolidate resources onto centralized servers on the network.

This chapter focuses on fundamental NFS concepts and supplemental information.

Samba

- Introduction to Samba

- Samba Daemons and Related Services

- Connecting to a Samba Share

- Configuring a Samba Server

- Starting and Stopping Samba

- Samba Server Types and the

smb.confFile - Samba Server Types and the

- Samba Security Modes

- Samba Account Information Databases

- Samba Network Browsing

- Samba with CUPS Printing Support

- Samba Distribution Programs

- Additional Resources

Samba is an open source implementation of the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol. It allows the networking of Microsoft Windows, Linux, UNIX, and other operating systems together, enabling access to Windows-based file and printer shares. Samba's use of SMB allows it to appear as a Windows server to Windows clients.

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) is a network protocol that automatically assigns TCP/IP information to client machines. Each DHCP client connects to the centrally located DHCP server, which returns that client's network configuration (including the IP address, gateway, and DNS servers).

Apache HTTP Server

The Apache HTTP Server is a robust, commercial-grade open source Web server developed by the Apache Software Foundation (http://www.apache.org/). Community Enterprise Linux includes the Apache HTTP Server 2.2 as well as a number of server modules designed to enhance its functionality.

The default configuration file installed with the Apache HTTP Server works without alteration for most situations. This chapter outlines many of the directives found within its configuration file (/etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf) to aid those who require a custom configuration or need to convert a configuration file from the older Apache HTTP Server 1.3 format.

Warning

If using the graphical HTTP Configuration Tool (system-config-httpd ), do not hand edit the Apache HTTP Server's configuration file as the HTTP Configuration Tool regenerates this file whenever it is used.

FTP

File Transfer Protocol (FTP) is one of the oldest and most commonly used protocols found on the Internet today. Its purpose is to reliably transfer files between computer hosts on a network without requiring the user to log directly into the remote host or have knowledge of how to use the remote system. It allows users to access files on remote systems using a standard set of simple commands.

This chapter outlines the basics of the FTP protocol, as well as configuration options for the primary FTP server shipped with Community Enterprise Linux, vsftpd.

The birth of electronic mail (email) occurred in the early 1960s. The mailbox was a file in a user's home directory that was readable only by that user. Primitive mail applications appended new text messages to the bottom of the file, making the user wade through the constantly growing file to find any particular message. This system was only capable of sending messages to users on the same system.

The first network transfer of an electronic mail message file took place in 1971 when a computer engineer named Ray Tomlinson sent a test message between two machines via ARPANET - the precursor to the Internet. Communication via email soon became very popular, comprising 75 percent of ARPANET's traffic in less than two years.

Today, email systems based on standardized network protocols have evolved into some of the most widely used services on the Internet. Community Enterprise Linux offers many advanced applications to serve and access email.

This chapter reviews modern email protocols in use today and some of the programs designed to send and receive email.

Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP)

The Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) is a set of open protocols used to access centrally stored information over a network. It is based on the X.500 standard for directory sharing, but is less complex and resource-intensive. For this reason, LDAP is sometimes referred to as "X.500 Lite." The X.500 standard is a directory that contains hierarchical and categorized information, which could include information such as names, addresses, and phone numbers.

Like X.500, LDAP organizes information in a hierarchal manner using directories. These directories can store a variety of information and can even be used in a manner similar to the Network Information Service (NIS), enabling anyone to access their account from any machine on the LDAP enabled network.

In many cases, LDAP is used as a virtual phone directory, allowing users to easily access contact information for other users. But LDAP is more flexible than a traditional phone directory, as it is capable of referring a querent to other LDAP servers throughout the world, providing an ad-hoc global repository of information. Currently, however, LDAP is more commonly used within individual organizations, like universities, government departments, and private companies.

LDAP is a client/server system. The server can use a variety of databases to store a directory, each optimized for quick and copious read operations. When an LDAP client application connects to an LDAP server, it can either query a directory or attempt to modify it. In the event of a query, the server either answers the query locally, or it can refer the querent to an LDAP server which does have the answer. If the client application is attempting to modify information within an LDAP directory, the server verifies that the user has permission to make the change and then adds or updates the information.

This chapter refers to the configuration and use of OpenLDAP 2.0, an open source implementation of the LDAPv2 and LDAPv3 protocols.

Authentication Configuration

When a user logs in to a Community Enterprise Linux system, the username and password combination must be verified, or authenticated, as a valid and active user. Sometimes the information to verify the user is located on the local system, and other times the system defers the authentication to a user database on a remote system.

The Authentication Configuration Tool provides a graphical interface for configuring user information retrieval from NIS, LDAP, and Hesiod servers. This tool also allows you to configure LDAP, Kerberos, and SMB as authentication protocols.

Note

If you configured a medium or high security level during installation (or with the Security Level Configuration Tool), then the firewall will prevent NIS (Network Information Service) authentication.

This chapter does not explain each of the different authentication types in detail. Instead, it explains how to use the Authentication Configuration Tool to configure them.

To start the graphical version of the Authentication Configuration Tool from the desktop, select the System (on the panel) > > or type the command system-config-authentication at a shell prompt (for example, in an XTerm or a GNOME terminal).

Important

After exiting the authentication program, the changes made take effect immediately.

Using and Caching Credentials with SSSD

The System Security Services Daemon (SSSD) provides access to different identity and authentication providers. SSSD is an intermediary between local clients and any configured data store. The local clients connect to SSSD and then SSSD contacts the external providers. This brings a number of benefits for administrators:

- Reducing the load on identification/authentication servers. Rather than having every client service attempt to contact the identification server directly, all of the local clients can contact SSSD which can connect to the identification server or check its cache.

- Permitting offline authentication. SSSD can optionally keep a cache of user identities and credentials that it retrieves from remote services. This allows users to authenticate to resources successfully, even if the remote identification server is offline or the local machine is offline.

- Using a single user account. Remote users frequently have two (or even more) user accounts, such as one for their local system and one for the organizational system. This is necessary to connect to a virtual private network (VPN). Because SSSD supports caching and offline authentication, remote users can connect to network resources simply by authenticating to their local machine and then SSSD maintains their network credentials.

The System Security Services Daemon does not require any additional configuration or tuning to work with the Authentication Configuration Tool. However, SSSD can work with other applications, and the daemon may require configuration changes to improve the performance of those applications.

Console Access

When normal (non-root) users log into a computer locally, they are given two types of special permissions:

- They can run certain programs that they would otherwise be unable to run.

- They can access certain files (normally special device files used to access diskettes, CD-ROMs, and so on) that they would otherwise be unable to access.

Since there are multiple consoles on a single computer and multiple users can be logged into the computer locally at the same time, one of the users has to essentially win the race to access the files. The first user to log in at the console owns those files. Once the first user logs out, the next user who logs in owns the files.

In contrast, every user who logs in at the console is allowed to run programs that accomplish tasks normally restricted to the root user. If X is running, these actions can be included as menu items in a graphical user interface. As shipped, these console-accessible programs include

halt,poweroff, andreboot.Date and Time Configuration

The Time and Date Properties Tool allows the user to change the system date and time, to configure the time zone used by the system, and to setup the Network Time Protocol (NTP) daemon to synchronize the system clock with a time server.

You must be running the X Window System and have root privileges to use the tool. There are three ways to start the application:

- From the desktop, go to Applications (the main menu on the panel) > >

- From the desktop, right-click on the time in the toolbar and select .

- Type the command

system-config-date,system-config-time, ordateconfigat a shell prompt (for example, in an XTerm or a GNOME terminal).

The X Window System

While the heart of Community Enterprise Linux is the kernel, for many users, the face of the operating system is the graphical environment provided by the X Window System, also called X.

Other windowing environments have existed in the UNIX world, including some that predate the release of the X Window System in June 1984. Nonetheless, X has been the default graphical environment for most UNIX-like operating systems, including Community Enterprise Linux, for many years.

The graphical environment for Community Enterprise Linux is supplied by the X.Org Foundation, an open source organization created to manage development and strategy for the X Window System and related technologies. X.Org is a large-scale, rapidly developing project with hundreds of developers around the world. It features a wide degree of support for a variety of hardware devices and architectures, and can run on a variety of different operating systems and platforms. This release for Community Enterprise Linux specifically includes the X11R7.1 release of the X Window System.

The X Window System uses a client-server architecture. The X server (the Xorg binary) listens for connections from X client applications via a network or local loopback interface. The server communicates with the hardware, such as the video card, monitor, keyboard, and mouse. X client applications exist in the user-space, creating a graphical user interface (GUI) for the user and passing user requests to the X server.

X Window System Configuration

During installation, the system's monitor, video card, and display settings are configured. To change any of these settings after installation, use the X Configuration Tool.

To start the X Configuration Tool, go to System (on the panel) > > , or type the command system-config-display at a shell prompt (for example, in an XTerm or GNOME terminal). If the X Window System is not running, a small version of X is started to run the program.

After changing any of the settings, log out of the graphical desktop and log back in to enable the changes.

Users and Groups

The control of users and groups is a core element of Community Enterprise Linux system administration.

Users can be either people (meaning accounts tied to physical users) or accounts which exist for specific applications to use.

Groups are logical expressions of organization, tying users together for a common purpose. Users within a group can read, write, or execute files owned by that group.

Each user and group has a unique numerical identification number called a userid (UID) and a groupid (GID), respectively.

A user who creates a file is also the owner and group owner of that file. The file is assigned separate read, write, and execute permissions for the owner, the group, and everyone else. The file owner can be changed only by the root user, and access permissions can be changed by both the root user and file owner.

Community Enterprise Linux also supports access control lists (ACLs) for files and directories which allow permissions for specific users outside of the owner to be set. For more information about ACLs, refer to Chapter 9, Access Control Lists.

Printer Configuration

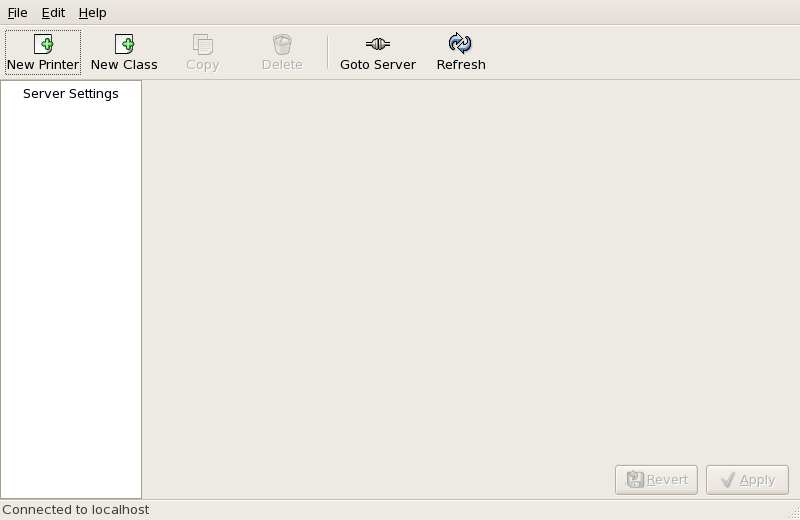

Printer Configuration Tool allows users to configure a printer. This tool helps maintain the printer configuration file, print spool directories, print filters, and printer classes.

Community Enterprise Operating System.8 uses the Common Unix Printing System (CUPS). If a system was upgraded from a previous Community Enterprise Linux version that used CUPS, the upgrade process preserves the configured queues.

Using Printer Configuration Tool requires root privileges. To start the application, select System (on the panel) > > , or type the command system-config-printer at a shell prompt.

Main window

Figure 36.1. Printer Configuration Tool

The following types of print queues can be configured:

- - a printer connected directly to the network through HP JetDirect or Appsocket interface instead of a computer.

- - a printer that can be accessed over a TCP/IP network via the Internet Printing Protocol (for example, a printer attached to another Community Enterprise Linux system running CUPS on the network).

- - a printer attached to a different UNIX system that can be accessed over a TCP/IP network (for example, a printer attached to another Community Enterprise Linux system running LPD on the network).

- - a printer attached to a different system which is sharing a printer over an SMB network (for example, a printer attached to a Microsoft Windows™ machine).

- - a printer connected directly to the network through HP JetDirect instead of a computer.

Important

If you add a new print queue or modify an existing one, you must apply the changes for them to take effect.

Clicking the button prompts the printer daemon to restart with the changes you have configured.

Clicking the button discards unapplied changes.

Automated Tasks

In Linux, tasks can be configured to run automatically within a specified period of time, on a specified date, or when the system load average is below a specified number. Community Enterprise Linux is pre-configured to run important system tasks to keep the system updated. For example, the slocate database used by the locate command is updated daily. A system administrator can use automated tasks to perform periodic backups, monitor the system, run custom scripts, and more.

Community Enterprise Linux comes with several automated tasks utilities: cron, at, and batch.

Log Files

Log files are files that contain messages about the system, including the kernel, services, and applications running on it. There are different log files for different information. For example, there is a default system log file, a log file just for security messages, and a log file for cron tasks.

Log files can be very useful when trying to troubleshoot a problem with the system such as trying to load a kernel driver or when looking for unauthorized log in attempts to the system. This chapter discusses where to find log files, how to view log files, and what to look for in log files.

Some log files are controlled by a daemon called syslogd. A list of log messages maintained by syslogd can be found in the /etc/syslog.conf configuration file.

SystemTap

Gathering System Information

Before you learn how to configure your system, you should learn how to gather essential system information. For example, you should know how to find the amount of free memory, the amount of available hard drive space, how your hard drive is partitioned, and what processes are running. This chapter discusses how to retrieve this type of information from your Community Enterprise Linux system using simple commands and a few simple programs.

OProfile

OProfile is a low overhead, system-wide performance monitoring tool. It uses the performance monitoring hardware on the processor to retrieve information about the kernel and executables on the system, such as when memory is referenced, the number of L2 cache requests, and the number of hardware interrupts received. On a Community Enterprise Linux system, the oprofile RPM package must be installed to use this tool.

Many processors include dedicated performance monitoring hardware. This hardware makes it possible to detect when certain events happen (such as the requested data not being in cache). The hardware normally takes the form of one or more counters that are incremented each time an event takes place. When the counter value, essentially rolls over, an interrupt is generated, making it possible to control the amount of detail (and therefore, overhead) produced by performance monitoring.

OProfile uses this hardware (or a timer-based substitute in cases where performance monitoring hardware is not present) to collect samples of performance-related data each time a counter generates an interrupt. These samples are periodically written out to disk; later, the data contained in these samples can then be used to generate reports on system-level and application-level performance.

OProfile is a useful tool, but be aware of some limitations when using it:

- Use of shared libraries - Samples for code in shared libraries are not attributed to the particular application unless the

--separate=libraryoption is used.

- Performance monitoring samples are inexact - When a performance monitoring register triggers a sample, the interrupt handling is not precise like a divide by zero exception. Due to the out-of-order execution of instructions by the processor, the sample may be recorded on a nearby instruction.

opreportdoes not associate samples for inline functions' properly -opreportuses a simple address range mechanism to determine which function an address is in. Inline function samples are not attributed to the inline function but rather to the function the inline function was inserted into.- OProfile accumulates data from multiple runs - OProfile is a system-wide profiler and expects processes to start up and shut down multiple times. Thus, samples from multiple runs accumulate. Use the command

opcontrol --resetto clear out the samples from previous runs. - Non-CPU-limited performance problems - OProfile is oriented to finding problems with CPU-limited processes. OProfile does not identify processes that are asleep because they are waiting on locks or for some other event to occur (for example an I/O device to finish an operation).

Manually Upgrading the Kernel

The Community Enterprise Linux kernel is custom built by the Community Enterprise Linux kernel team to ensure its integrity and compatibility with supported hardware. Before CentOS releases a kernel, it must first pass a rigorous set of quality assurance tests.

Community Enterprise Linux kernels are packaged in RPM format so that they are easy to upgrade and verify using the Package Management Tool, or the yum command. The Package Management Tool automatically queries the Community Enterprise Linux servers and determines which packages need to be updated on your machine, including the kernel. This chapter is only useful for those individuals that require manual updating of kernel packages, without using the yum command.

Warning

Building a custom kernel is not supported by the CentOS Global Services Support team, and therefore is not explored in this manual.

Tip

The use of yum is highly recommended by CentOS for installing upgraded kernels.

For more information on CentOS Network, the Package Management Tool, and yum, refer to Chapter 14, Product Subscriptions and Entitlements.

General Parameters and Modules

This chapter is provided to illustrate some of the possible parameters available for common hardware device drivers [9], which under Community Enterprise Linux are called kernel modules. In most cases, the default parameters do work. However, there may be times when extra module parameters are necessary for a device to function properly or to override the module's default parameters for the device.

During installation, Community Enterprise Linux uses a limited subset of device drivers to create a stable installation environment. Although the installation program supports installation on many different types of hardware, some drivers (including those for SCSI adapters and network adapters) are not included in the installation kernel. Rather, they must be loaded as modules by the user at boot time.

Once installation is completed, support exists for a large number of devices through kernel modules.

Important

CentOS provides a large number of unsupported device drivers in groups of packages called kernel-smp-unsupported- and <kernel-version>kernel-hugemem-unsupported- . Replace <kernel-version><kernel-version> with the version of the kernel installed on the system. These packages are not installed by the Community Enterprise Linux installation program, and the modules provided are not supported by CentOS, Inc.

The kdump Crash Recovery Service

kdump is an advanced crash dumping mechanism. When enabled, the system is booted from the context of another kernel. This second kernel reserves a small amount of memory, and its only purpose is to capture the core dump image in case the system crashes. Since being able to analyze the core dump helps significantly to determine the exact cause of the system failure, it is strongly recommended to have this feature enabled.

This chapter explains how to configure, test, and use the kdump service in Community Enterprise Linux, and provides a brief overview of how to analyze the resulting core dump using the crash debugging utility.

Security Overview

Because of the increased reliance on powerful, networked computers to help run businesses and keep track of our personal information, industries have been formed around the practice of network and computer security. Enterprises have solicited the knowledge and skills of security experts to properly audit systems and tailor solutions to fit the operating requirements of the organization. Because most organizations are dynamic in nature, with workers accessing company IT resources locally and remotely, the need for secure computing environments has become more pronounced.

Unfortunately, most organizations (as well as individual users) regard security as an afterthought, a process that is overlooked in favor of increased power, productivity, and budgetary concerns. Proper security implementation is often enacted postmortem - after an unauthorized intrusion has already occurred. Security experts agree that the right measures taken prior to connecting a site to an untrusted network, such as the Internet, is an effective means of thwarting most attempts at intrusion.

Securing Your Network

Security and SELinux

Working With SELinux

- End User Control of SELinux

- Administrator Control of SELinux

-

- Viewing the Status of SELinux

- Relabeling a File System

- Managing NFS Home Directories

- Granting Access to a Directory or a Tree

- Backing Up and Restoring the System

- Enabling or Disabling Enforcement

- Enable or Disable SELinux

- Changing the Policy

- Specifying the Security Context of Entire File Systems

- Changing the Security Category of a File or User

- Running a Command in a Specific Security Context

- Useful Commands for Scripts

- Changing to a Different Role

- When to Reboot

- Relabeling a File System

- Viewing the Status of SELinux

- Analyst Control of SELinux

SELinux presents both a new security paradigm and a new set of practices and tools for administrators and some end-users. The tools and techniques discussed in this chapter focus on standard operations performed by end-users, administrators, and analysts.

Customizing SELinux Policy

CentOS Training and Certification

Certification Tracks

- CentOS Certified Technician (RHCT)

-

Now entering its third year, CentOS Certified Technician is the fastest-growing credential in all of Linux, with currently over 15,000 certification holders. RHCT is the best first step in establishing Linux credentials and is an ideal initial certification for those transitioning from non-UNIX/ Linux environments.

CentOS certifications are indisputably regarded as the best in Linux, and perhaps, according to some, in all of IT. Taught entirely by experienced CentOS experts, our certification programs measure competency on actual live systems and are in great demand by employers and IT professionals alike.

Choosing the right certification depends on your background and goals. Whether you have advanced, minimal, or no UNIX or Linux experience whatsoever, CentOS Training has a training and certification path that is right for you.

- CentOS Certified Engineer (RHCE)

-

CentOS Certified Engineer began in 1999 and has been earned by more than 20,000 Linux experts. Called the "crown jewel of Linux certifications," independent surveys have ranked the RHCE program #1 in all of IT.

- CentOS Certified Security Specialist (RHCSS)

-

An RHCSS has RHCE security knowledge plus specialized skills in Community Enterprise Linux, CentOS Directory Server and SELinux to meet the security requirements of today's enterprise environments. RHCSS is CentOS's newest certification, and the only one of its kind in Linux.

- CentOS Certified Architect (RHCA)

-

RHCEs who seek advanced training can enroll in Enterprise Architect courses and prove their competency with the newly announced CentOS Certified Architect (RHCA) certification. RHCA is the capstone certification to CentOS Certified Technician (RHCT) and CentOS Certified Engineer (RHCE), the most acclaimed certifications in the Linux space.

RH033: CentOS Linux Essentials

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rh033.html

RH035: CentOS Linux Essentials for Windows Professionals

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rh035.html

RH133: CentOS Linux System Administration and CentOS Certified Technician (RHCT) Certification

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rh133.html

RH202 RHCT EXAM - The fastest growing credential in all of Linux.

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rh202.html

- RHCT exam is included with RH133. It can also be purchased on its own for $349

- RHCT exams occur on the fifth day of all RH133 classes

RH253 CentOS Linux Networking and Security Administration

RH300: RHCE Rapid track course (and RHCE exam)

The fastest path to RHCE certification for experienced UNIX/Linux users.

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rh300.html

RH302 RHCE EXAM

- RHCE exams are included with RH300. It can also be purchased on its own.

- RHCE exams occur on the fifth day of all RH300 classes

http://www.redhat.com/training/rhce/courses/rhexam.html

RHS333: Community Enterprise security: network services

Security for the most commonly deployed services.

http://www.redhat.com/training/architect/courses/rhs333.html

RH401: Community Enterprise Deployment and systems management

Manage Community Enterprise Linux deployments.

http://www.redhat.com/training/architect/courses/rh401.html

RH423: Community Enterprise Directory services and authentication

Manage and deploy directory services for Community Enterprise Linux systems.

http://www.redhat.com/training/architect/courses/rh423.html

SELinux Courses

RH436: Community Enterprise storage management

Deploy and manage CentOS's cluster file system technology.

Equipment-intensive:

- five servers

- storage array

http://www.redhat.com/training/architect/courses/rh436.html

RH442: Community Enterprise system monitoring and performance tuning

Performance tuning and capacity planning for Community Enterprise Linux

http://www.redhat.com/training/architect/courses/rh442.html

Community Enterprise Linux Developer Courses

JBoss Courses