Introducing Tk

Introducing Tk

Tk (pronounced tee-kay) is an extension of Tcl. Tk provides an X Window system-based toolkit you can use in Tcl scripts to build GUIs. As you might expect, Tk provides a set of Tcl commands beyond the core built-in set. You can use these Tk commands to create windows, menus, buttons, and other user-interface components and to provide a GUI for your Tcl scripts.

As with anything new, you can best learn Tk through examples, which the following sections provide.

Saying "Hello, World!" in Tk

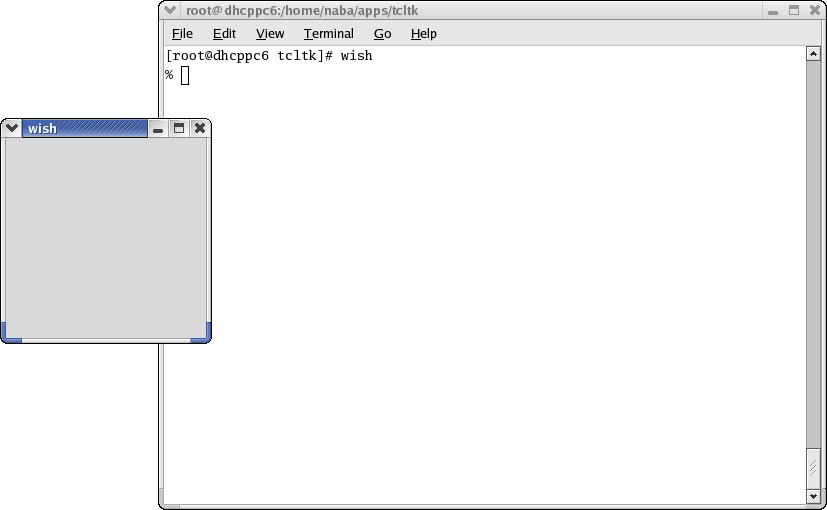

Tk is a major-enough extension to Tcl to warrant its own shell, called wish (the windowing shell). The wish shell interprets all built-in Tcl commands, as well as the Tk commands. You must start X before you can run wish; after all, wish enables you to use X to create graphical interfaces.

The wish program should be in the /usr/bin directory, which should be in your PATH environment variable by default. To start wish, all you have to do is type the following at the shell prompt in a terminal window:

wish %

The wish program displays its prompt (the percent sign) and a small window, as shown in the upper-right corner of Figure 25-1.

Therefore, wish provides an interactive prompt from which you can enter Tk commands to create a graphical interface. As wish interprets the commands, it displays the resulting graphical interface in the window.

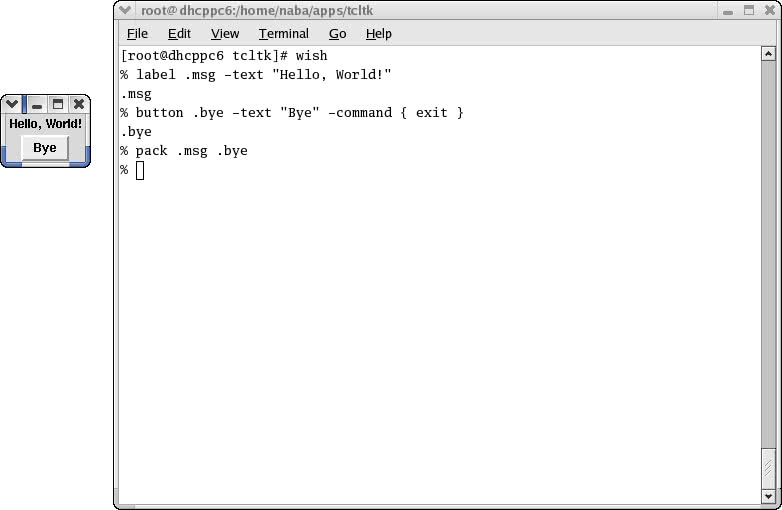

To see how this interactive creation of graphical interface works, try the following commands at the wish prompt):

% label .msg -text "Hello, World!"

.msg

% button .bye -text "Bye" -command { exit }

.bye

% pack .msg .bye

%

Figure 25-2 shows the result of these commands; wish displays a Hello, World! label with a Bye button below it.

Notice that the label and the button do not appear until you enter the pack command. In addition, the wish window shrinks to a size just large enough to hold the label and the button.

Click the Bye button; the wish program exits. This is because the -command { exit } argument of the button command associates the Tcl command exit with a click of the Bye button.

To create a Tk program or script that displays the Hello, World! label and the Bye button, all you have to do is place the Tk commands in a file and add a special line at the beginning to ensure that the wish shell processes the file. To do so, follow these steps:

-

Use a text editor to enter and save the following lines in a file named

hellotk:#!/usr/bin/wish # A simple Tk script label .msg -text "Hello, World!" button .bye -text "Bye" -command { exit } pack .msg .bye -

Type the following command at the shell prompt to make the

hellotkfile executable (that's what the+xin the chmod command means):chmod +x hellotk

-

To run the

hellotkscript, type the following at the shell prompt in a terminal window:./hellotk

Figure 25-3 shows the window with a Hello, World! label and the Bye button that should appear when you run the hellotk script. Click the Bye button to close the window and end the script.

As this example shows, the basic steps for writing a Tk script are the same as those for creating and running any Tcl script. The only difference is that the Tk commands generate graphical output.

Learning Tk Widget Basics

Now that you have been exposed to Tcl, you can begin writing Tk scripts. What you need to know are the Tk commands used to create and configure widgets.

As you create a widget, you can specify many of its characteristics as arguments of the command. You can, for example, create a blue button with a red label (test) and display the button by using the following commands:

button .b -text test -fg red -bg blue pack .b

The pack command does not create a widget; rather, it positions a widget in relation to others. Table 25-5 lists all the widget-manipulation commands.

| Insider Insight |

To look up online help about any Tk command listed in Tables 25-4 and 25-5, type |

|

Command |

Action |

|---|---|

|

|

Executes a command after a specified amount of time elapses |

|

|

Associates a Tcl command with an X event, so that the Tcl command is automatically invoked whenever the X event occurs |

|

|

Destroys one or more widgets |

|

|

Directs keyboard events to a particular window (gives that window the input focus) |

|

|

Confines pointer and keyboard events to a specified widget and its children |

|

|

Lowers a window in the stacking order. (The stacking order refers to the order in which various windows overlap one another on the display screen.) |

|

|

Provides access to the X resource database |

|

|

Automatically positions widgets in a frame, based on specified constraints |

|

|

Allows manual positioning of a widget relative to another widget |

|

|

Raises a window's position in the stacking order |

|

|

Manipulates the X PRIMARY selection (the standard name of a selection in X) |

|

|

Sends a Tcl command to a different Tk application (used for interprocess communications) |

|

|

Provides information about the internal state of the Tk interpreter |

|

|

Handles any error that occurs in Tk applications (the interpreter calls this command when errors occur in Tk applications) |

|

|

Waits for an event, such as the destruction of a window, or a change in the value of a variable |

|

|

Processes all pending events and updates the display |

|

|

Returns information about a widget |

|

|

Provides access to the window manager. (You can send commands to the window manager, requesting a size for your top-level window, for example.) |

Defining Widget Hierarchies in Tk

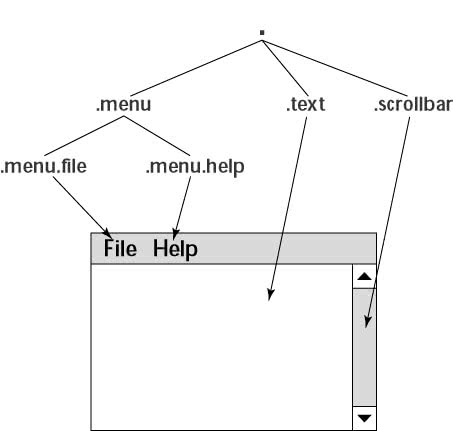

From the example that creates a label and a button, you may have guessed that the argument that follows the widget-creation command is the widget's name. If you are wondering why all the names start with a period, which is required at the beginning of a widget's name, it is because widgets are organized in a hierarchy.

Suppose that you have a main window that contains a menu bar, a text area, and a scroll bar. The menu bar has two buttons, labeled File and Help. Figure 25-4 shows this widget hierarchy as it appears onscreen; it also shows how the widget names relate to this hierarchy.

Configuring Widgets

Tk treats each widget name as a command name. You can perform operations on a specific widget by using that widget's name, followed by arguments that make sense for that widget. If you have a button named .b, for example, use the following command to set that button's background to blue:

.b config -fg blue

You can change the button's label to Goodbye! by using the following command:

.b config -text Goodbye!

The arguments -fg blue and -text Goodbye! specify the attributes of a widget. Each attribute name begins with a hyphen (-), as in -text. The next argument is that attribute's value.

Displaying Widgets

Tk does not display a widget, until you use a command to position the widget in the main window. To display the widgets, you have to use a geometry manager-a Tk procedure that arranges one or more child widgets in a parent widget.

Using the pack Command

The pack command is the most commonly used geometry-management command in Tk. As some of the simple examples in this chapter show, to make a button named .btn1 appear, use pack as follows:

pack .btn1

You can specify several widget names on the same pack command line. To display the buttons .btn1, .btn2, and .btn3, arranged in a vertical line in that order, use the following:

pack .btn1 .btn2 .btn3

On a menu bar, for instance, this type of pack command makes the most efficient use of the available space.

Table 25-6 summarizes the pack command's syntax. As Table 25-6 shows, you can use the pack command to position widgets and get information about the widget hierarchy.

|

Command |

Description |

|---|---|

|

|

Packs the listed widgets according to the specified |

|

|

Packs the listed widgets according to the specified options |

|

|

Hides (unpacks) the specified widgets |

|

|

Returns the packing configuration (a list of options and values) of the specified |

|

|

If |

|

|

Returns the list of widgets managed by a specified widget If you want a more complicated layout of widgets, you have to use the packing options shown in Table 25-7. |

|

|

Places the widget that is being packed after the widget specified by |

|

|

Determines where the managed widget is placed. (This applies only when the containing widget is larger than the managed widget.) The |

|

|

Places the widget that is being packed before the widget specified by |

|

|

If |

|

|

Indicates how to expand the containing widget, if it becomes bigger than what the widgets contained in it require. The |

|

|

Indicates the widget in which the widgets specified in the pack command line are placed. If you do not use this option, widgets are packed in their parent widget ( |

|

|

Specifies extra horizontal space inside the widget being packed (in addition to the space that it already needs). The |

|

|

Specifies extra vertical space inside the widget being packed (in addition to the space it already needs). The |

|

|

Specifies extra horizontal space outside the border of the widget that is being packed. The |

|

|

Specifies extra vertical space outside the border of the widget being packed. The |

|

|

Packs against the specified side. The |

Using the place Command

The place command is a simpler way to specify the placement of widgets as compared to the pack command, but you have to position all the windows yourself. It is simpler than pack because the place command gives you direct control of the widget positions. On the other hand, direct control of widget placement is fine for a few windows, but it can get tedious in a hurry when you have many widgets in a user interface.

Using place, you can position a widget at a specific location. For example, to place .btn1 at the coordinate (100, 50) in its parent widget, use the following command:

place .btn1 -x 100 -y 50

A good use of place is to center a widget within its parent widget. For this purpose, use the -relx and -rely options of place. If .f is a frame widget (a widget that contains other widgets), you can display it at the center of the parent window by using the following commands:

frame .f button .f.b1 -text Configure button .f.b2 -text Quit pack .f.b1 .f.b2 -side left place .f -relx 0.5 -rely 0.5 -anchor center

As the code fragment shows, the buttons inside the frame are packed with the pack command. Only the frame, .f, is positioned with the place command. The -relx and -rely options enable you to specify the relative positions in terms of a fraction of the containing widget's size. A zero value for -relx means the left edge; 1 is the right edge; and 0.5 means the middle.

Like pack, the place command has several forms, listed in Table 25-8.

|

Command |

Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Positions the listed widgets according to the specified | ||

|

|

Positions the listed widgets according to the specified options | ||

|

|

Stops managing the specified widgets and unmaps (hides) them | ||

|

|

Returns the list of options and their values for the specified widget | ||

|

|

Returns the list of widgets managed by the specified widget In addition, Option

Description

| ||

|

|

Specifies which point of the managed widget is placed in the specified position in the managing window. The | ||

|

|

Indicates how the managing widget's borders are used when the managed widgets are positioned. The | ||

|

|

Specifies the height of the managed widget | ||

|

|

Indicates the widget relative to which the positions of the widgets specified in the place command line are specified. If you do not use this option, widgets are placed relative to their parent widgets ( | ||

|

|

Specifies the height of the managed widget as a fraction of the managing widget. The fraction is a floating-point value. | ||

|

|

Specifies the width of the managed widget as a fraction of the managing widget. The fraction is a floating-point value. | ||

|

|

Specifies the horizontal position of the managed widget as a fraction of the managing widget's width. The | ||

|

|

Specifies the vertical position of the managed widget as a fraction of the managing widget's height. The | ||

|

|

Specifies the horizontal position of the managed widget's anchor point in the managing widget. The | ||

|

|

Specifies the vertical position of the managed widget's anchor point in the managing widget. The | ||

|

|

Specifies the width of the managed widget |

Binding Actions to Events

When you write a program that has a graphical user interface, various program actions are initiated by events, such as the user clicking a button in the user interface. In a Tk script, you indicate what the program does by associating actions with events. In this case, an action is simply a Tcl script that performs some task. In the case of a Quit button, for example, a logical action is the Tcl command exit, which ends the Tk script.

For buttons, a click of the button is a simple way to form this association. Use the command option of the button command to specify a Tcl command to be executed when the user clicks the button. The exit command is associated with the Quit button as follows:

button .b -text Quit -command { exit }

| Insider Insight |

The curly braces are not necessary when you have only one Tcl command, but you must enclose multiple commands inside braces. |

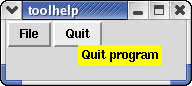

To see a more detailed example of how to bind an action to an event, consider this scenario. You may have noticed that many Microsoft Windows applications, as well as GNOME and KDE applications, sport a toolbar-essentially, a collection of buttons, each of which is meant to perform a specific task. Typically, each button bears an icon that indicates its purpose. To help users learn the meaning of a button quickly, many Windows applications have a feature called tool help. If you place the mouse pointer on a button, a small window pops up, displaying a short help message that tells you what the button does.

You can use Tk to implement a similar tool-help feature. Follow these steps:

-

Create the button.

-

Prepare the help message as a label (preferably with a bright background, such as yellow).

-

When the mouse pointer enters a button, an Enter event occurs. Bind the Enter event to a command that makes the help label visible. Use the

placecommand to position the label relative to the button, so that the tool help label always appears near the associated button. The following example shows howbindis used to associate theplacecommand (shown within braces) with the Enter event:bind .f.q <Enter> { place .bh -in .f.q -relx 0.5 -rely 1.0 } -

When the mouse pointer leaves the button, a Leave event occurs. Bind the Leave event to the

place forgetcommand to hide the help message, as follows:bind .f.q <Leave> { place forget .bh }

The following sample toolhelp script demonstrates how to implement tool help in Tk:

#!/usr/bin/wish -f

# Demonstrates a "tool help" window that appears when you

# place the mouse pointer inside the Quit button.

wm geometry . 180x60

frame .f

button .f.b -text File

label .bh -text "Quit program"

.bh config -bg yellow

button .f.q -text Quit -command { exit }

bind .f.q <Enter> { place .bh -in .f.q -relx 0.5 -rely 1.0 }

bind .f.q <Leave> { place forget .bh }

pack .f.b .f.q -side left

pack .f -fill x

Make the toolhelp script file executable by using the chmod +x toolhelp command. Then run that script by typing ./toolhelp at the shell prompt in a terminal window. Figure 25-5 shows the window that results after you place the mouse pointer on the Quit button.

When you use bind to associate a Tcl script with an event, you need to know how to specify the event. Most are either keyboard events or mouse events. A smaller number of events are related to the state of a widget's window. <Map> and <Unmap> events, for example, occur when a widget is managed or unmanaged (when you use pack forget or place forget).

Understanding Keyboard Events

There are two keyboard events:

-

<

KeyPress> occurs when you press a key. -

<

KeyRelease> occurs when you release a key.

You can specify a keyboard event for a specific key by appending that key's keysym (which is the X Window system's standard name for a key) to the string KeyPress- and enclosing everything in angle brackets. The event associated with pressing the q key, for example, is specified by <Keypress-q>. Tk provides a shorter format for keyboard events. You can simply place the keysym inside angle brackets, as follows:

<q>

For most key presses, the event specification is straightforward. If you want to exit when the user presses Ctrl-C inside a widget named .text, use the bind command as follows:

bind .text <Control-c> exit

Table 25-10 shows some other commonly used keysyms.

|

Keysym |

Name of Key |

|---|---|

|

|

Backspace |

|

|

Comma |

|

|

Down arrow |

|

|

Dollar sign ( |

|

|

Escape |

|

|

Exclamation mark |

|

|

Left arrow |

|

|

Number sign ( |

|

|

Period |

|

|

Enter |

|

|

Right arrow |

|

|

Tab |

|

|

Up arrow |

Understanding Mouse Events

Use <ButtonPress> and <ButtonRelease> to denote mouse-button click and release events, respectively. You have to append the button number to make the event specific. Thus, clicking the left mouse button (which is button 1 in X terminology) is denoted by <ButtonPress-1>. A shorthand notation for button presses is to omit Press; thus, you can write <Button-1> to denote the event generated by clicking the left mouse button.

Understanding Window Events

In addition to keyboard and mouse events, X includes many events that occur when a window is manipulated. The X server generates <Map> and <Unmap> events, for example, when a widget is displayed or hidden (by the pack or place command).

A <Configure> event occurs when the user resizes a window. Thus, you can bind a <Configure> event to a redisplay procedure that redraws the contents of a widget based on the new size.

A <Destroy> event occurs when a window is about to be destroyed. Bind a procedure to the <Destroy> event, and intercept requests to delete a window.