JSP has come to be the dominant view technology for J2EE web apps, largely because it is blessed by Sun as a core part of J2EE. JSP views offer the following benefits:

They're easy to develop. Recompilation on request (at least during development) means rapid develop-deploy cycles.

Sandardization is usually a good thing. However, there is a danger that a flawed solution can be used too widely merely because it is a standard. JSP also has such significant drawbacks as a view technology that is questionable whether it would have survived with Sun's imprimatur:

JSP's origins predate the use of MVC for web apps and it shows. The JSP coding model owes much to Microsoft's Active Server Pages (ASP), which dates back to 1996. ASP uses similar syntax and the same model of escaping between executable script and static markup. Microsoft has recently moved away from this model, as experience has shown that ASP apps become messy and unmaintainable.

In practice, the negatives associated with JSP are surprisingly harmful. For background reading on the drawbacks of JSP pages, see the following articles among the many that have been published on the subject:

http://www.servlets.com/soapbox/problems-jsp.html. An early and often-quoted contribution to the JSP debate by Jason Hunter, the author of several tutorials on servlets.

In the remainder of this section, we'll look at how to enjoy the advantages of JSP without suffering from its disadvantages. Essentially, this amounts to minimizing the amount of Java code in JSP pages. The following is a discussion of how to use the JSP infrastructure in maintainable web apps, not a tutorial on the JSP infrastructure itself. Please refer to reference material on JSP if necessary.

| Important |

An indication that JSP pages are being used correctly is when JSP pages do not violate the substitutability of views discussed in . For example, if a JSP is (inappropriately) used to handle requests, a JSP view could not be replaced by an XSLT view without breaking the functionality of the app. |

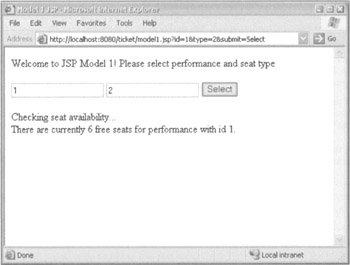

To demonstrate the consequences of misuse of JSP, let's look at an example of a JSP that isn't merely a view, but uses the power of Java to handle incoming requests ("Model 1" style) and uses J2EE APIs. As the control logic behind the "Show Reservation" view would make a JSP Model 1 version too lengthy, I've used a simple page that enables us to query seat availability by performance ID and seat type. A more realistic version of this page would present dropdowns allowing the user to input these values, but for the sake of the example I've neglected this, along with concern about the user entering non-numeric values. This JSP, mode11. jsp, both displays a form allowing the user to input performance and seat type, and processes the result. If the request is a form submission, the number of seats available will be displayed below the form; otherwise just the form will be displayed. The output of this page will look as follows:

The listing begins with imports of the Java objects used (both J2EE and app-specific). Note that we must use the JSP error page mechanism in the highlighted line to avoid the need to catch every exception that may occur on the page.

<%@ page errorPage="jsp/debug/debug.jsp" %>

<%@ page import="javax.naming.InitialContext" %> <%@ page import="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.boxoffice.BoxOffice" %> <%@ page import="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.exceptions.NoSuchPerformance Exception" %> <%@ page import="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.boxoffice.ejb. *" %

Next we declare a simple bean with properties matching the expected request parameters, so we don't need to work directly with the request. The ModellBean class is included in the source with the sample app: it simply exposes two int properties: id and type. Note the use of the <jsp:setProperty> standard action to populate these properties from request parameters. For the sake of the example, we won't worry about the user entering non-numeric input:

<jsp:useBean class="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.web.Mode11Bean" scope="session"> <jsp:setProperty property="*" /> </jsp:useBean>

Next there's a little template data:

<html> <head> <title>Model 1 JSP</title> </head> </body> Welcome to JSP Model 1! Please select performance and seat type

Whether processing a form submission or not, we will display the form. The form's fields will be prepopulated with the bean's property values, which will both be 0 on first displaying the page:

<form method="GET"> <input type="text" value="<jsp:getProperty property="id" />" /> <input type="text" value="<jsp:getProperty property="type" />" /> <input type="submit" value="Select" /> </form>

If this JSP isn't invoked by a form submission, this is all the content we'll see. If it is processing a form submission, which we can tell by checking for the presence of a submit request parameter, the scriptlet in the rest of the page takes effect. The scriptlet performs a JNDI lookup for the BoxOffice EJB. Once it obtains it, it queries it for the availability of seats for the performance id and seat type held in the bean. We make no effort to catch JNDI or EJB API errors, but let the JSP error page mechanism handle such errors. Adding additional try/catch blocks would be unacceptably complex. The output generated will vary whether or not there is a performance with the specified id. If there isn't, the BoxOffice getFreeSeatCount() method will throw a NoSuchPerformanceException, which the JSP catches, to provide an opportunity to generate different output. I've highlighted the lines that generate output, which account for less than half the source of the JSP:

<% if (request.getParameter("submit") != null) { %>

Checking seat availability...<br>

<%

int freeSeats = 0;

InitialContext ic = new InitialContext();

Object o = ic.lookup ("java:comp/env/ejb/BoxOffice");

BoxOfficeHome home = (BoxOfficeHome) ;

BoxOffice boxOffice = home.create();

try {

freeSeats = boxOffice.getFreeSeatCount (

queryBean.getId(), queryBean.getType());

%>

There are currently <%=freeSeats%> free seats

for performance with id <jsp:getProperty property="id"/>

<% } catch (NoSuchPerformanceException ex) { %>

There's no performance with id <jsp:getProperty property="id"/>. <br>Please try another id.

<% } } %>

Finally, some closing template data is displayed in any case:

</body> </html>

Although this JSP doesn't fulfill a realistic function, it does display problems seen in reality. Most experienced J2EE developers have seen - and had to clean up the problems caused by - many such JSP pages. What's wrong with this, and why will such JSP pages always prove a maintainability nightmare in real apps? The many problems include:

This JSP has two roles (displaying an input form and displaying the results of processing it), making it confusing to read.

In short, there's no separation between presentation and workflow: the one JSP handles everything, making it completely unintelligible to an HTML developer who might be asked to modify the appearance of the generated markup.

After this salutary negative example, let's look at how to write JSP pages that are maintainable. The data displayed in JSP pages normally comes from one or more JavaBeans declared on the page using the <jsp:useBean> standard action. In an MVC architecture, these beans will have been set as request attributes before the view is invoked. In some frameworks, controllers will set model data as request attributes. In our framework, an implementation of the View interface will expose model attributes as request parameters before forwarding to a JSP. The syntax for appropriate use of the <jsp:useBean> action within an MVC web app is as follows:

<jsp:useBean type="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.referencedata.Performance" scope="request" />

The value of the id attribute will be the name of the bean object, available to expressions, scriptlets, and actions. Note the scope attribute, which determines whether the bean value is set by an attribute value from the local JSP PageContext, the HttpRequest, the HttpSession (if one exists), or the global ServletContext. There are four values for scope: page, request, session, and app, of which only one (request) is compatible with correct use of JSP in an MVC web app, as views shouldn't access (and potentially manipulate) session or app-wide state.

| Note |

A bean of page scope is a local object, used within the current JSP. There are some situations in which this is appropriate, although I prefer to avoid object creation in JSP pages altogether. |

You might notice that I've omitted the optional class attribute, which specifies the fully-qualified bean implementation class, rather than the relevant type, which may be interface, as specified by the type parameter that I have used. By only specifying the type, and not the bean class, we've deprived the JSP of the ability to instantiate a new bean if none is found in the specified scope. It will throw a java.lang.InstantiationException instead. This is good practice, as unless the bean has been made available to the JSP as part of the model, the JSP should not have been invoked: we don't want it to fail mysteriously after automatically creating a new, unconfigured object in place of the missing model object. By specifying only the type, we retain flexibility in the controller (which can supply a model object of any type that implements the interface), and restrict the JSP's access to the bean to the most limited interface that's relevant: another good practice if interface inheritance is involved, or if the object is of a class that not only implements the interface but exposes other properties that are irrelevant to the view in question.

| Important |

Never allow the <jsp:useBean> action to create an object if none is found in scope by specifying the class attribute. A JSP should fail if required model data is not supplied. Use only request scope with the <jsp:useBean> action. This means that, as the default scope is page, we must always specify request scope explicitly. JSP pages should not access session or app objects; merely model data exposed by a controller. Even if some model data is also bound in the user's session, or shared with other users (and perhaps bound in the ServletContext), the controller should pass it to views as part of the model. Using this approach enables us to use any view technology, and to test views in isolation. |

As I noted in , the JSP request property-to-bean mapping mechanism is too naÏve to be usable in most real situations. It's also a danger to good design. Unfortunately, there is confusion in the way in which beans are supported in the JSP specification. A bean should really be a model for the page, but the mapping from request parameters onto bean properties means that beans can also be used as a way of helping the JSP handle the request. This is a JSP Model 1 approach, incompatible with an MVC architecture. It seemed plausible when the first version of the JSP specification was drawn up; experience has since shown this to be fatally flawed.

The most significant enhancement in JSP 1.1 was the introduction of custom tags, also known as tag extensions. These greatly enhance the power of JSP, but can be used inappropriately. Custom tags offer the following benefits:

They provide a neat way of moving code that would otherwise be in JSP pages into tag handler classes. For example, they can conceal the complexity of iteration over model data from JSP pages that use them.

However, custom tags also pose some dangers:

Custom tags add further temptation to use JSP for purposes other than as views. Far better than moving code out of a JSP to a custom tag is designing the web tier so that JSP pages don't need to contain code.

Custom tags have proven very popular, and they're now central to how JSP is used. Before we look at specific uses of custom tags, let's consider what role they should play in the MVC web app architecture we've described.

| Important |

If JSP pages are to be used as views, custom tags are view helpers. They're neither models nor controllers; they will principally be used to help display the models available to the JSP view. |

We shouldn't use custom tags to do things that are outside the role of views. For example, retrieving data from a database may be easy to implement in a tag handler, but is not the business of a JSP view. Moving the code into a tag handler class won't improve the fundamentally broken error handling. In general, enterprise access (such as EJB access and JNDI access) shouldn't be performed in tags. For this reason, I feel that tag libraries that offer simple database access and the like are dangerous, and should not be used in well-designed web apps. It's also not usually a good idea to use tags to output markup. Sometimes there's no alternative, but there are several reasons why it's best avoided:

If a custom tag generates markup, it limits the situations in which it can be used. It's the role of JSP pages that use the tag to control the appearance of the page.

Fortunately, custom tags can define scripting variables, letting JSP pages handle output formatting.

Since I started work on this tutorial, there has been a major milestone in JSP usability: the release of the JSP Standard Tag Library (JSTL 1.0). I consider this as more important than the release of JSP 1.2, which was a minor incremental step in the evolution of JSP. The JSTL offers the following:

An Expression Language (EL) that simplifies access to JavaBean properties and offers nested property support. This can be used in attributes passed to the tags in the library.

Of course none of these tags is original. The JSTL is a codification of the many variants of such tags many developers (including myself) have written since the release of JSP 1.1, but it's exciting because:

It's a standard, and thus is likely to become a lingua franca among JSP developers

I've seen and implemented many tag libraries, and my instinct is that JSTL has got it right: these tags are simple yet powerful, and intuitive to use. The only one of the JSTL tag libraries that is questionable is the SQL tag library. As the designers of the JSTL recognize, this shouldn't be used in well-designed apps. Its use is best restricted to prototypes or trivial apps. I won't discuss individual JSTL tags here, as I'll demonstrate the use of some of the most important in sample app code later in this chapter. The examples shipped with the Jakarta implementation are worth careful examination, displaying most common uses. The sample app uses the Apache implementation of the JSTL, available from http://jakarta.apache.org/taglibs/. I've found it very usable, although with a tendency to throw NullPointerExceptions that occasionally makes debugging more difficult than it should be.

| Important |

It's hard to overemphasize the importance of the JSP Standard Tag Library. This effectively adds a new language - the JSTL Expression Language - to JSP. As there were a lot of problems with the old approach of using Java scriptlets, and the JSP standard actions were inadequate to address many problems, this is a Very Good Thing. If you use JSP, learn and use the JSTL. Use the superior JSTL Expression Language in place of the limited <jsp:getProperty> standard action. Use JSTL iteration in place of for and while loops. However, don't use the SQL actions: RDBMS access has no place in view code, but is the job of business objects (not even web tier controllers). |

The Jakarta TagLibs site is a good source of other open-source tag libraries, and a good place to visit if you're considering implementing your own tag libraries. Many of the tags offered here, as elsewhere, are incompatible with the responsibility of JSP views, but they can still be of great value to us.

Especially interesting are caching tags, which can be used to boost performance by caching parts of JSP pages. Jakarta TagLibs has such tags in development, while OpenSymphony (http://www.opensymphony.com/) has a more mature implementation.

Although it's fairly easy to implement app-specific tag libraries, don't rush into it. Now that the JSTL is available, many app or site-specific tags are no longer necessary. For example, the JSTL Expression Language renders many app-specific tags designed to help display complex objects redundant (JSTL tags using the Expression Language can easily display complex data). I suggest the following guidelines if you are considering implementing your own tags:

Don't duplicate JSTL tags or the functionality of existing third-party tags. The more unique tags an app uses, the longer the learning curve for developers who will need to maintain it in future.

| Important |

Don't implement your own JSP custom tags without good reason. Especially given the power of the JSTL, many app-specific custom tags are no longer necessary. The more your own JSP dialect diverges from standard JSP plus the JSTL, the harder it will be to maintain your apps. |

Here are some guidelines for using custom tags, app-specific and standard:

Do use the JSTL: it almost always offers a superior alternative to scriptlets. JSTL will soon be universally understood by JSP developers, ensuring that pages using it are maintainable.

| Important |

A custom tag should be used as a refactoring of view logic out of a JSP view. It shouldn't conceal the implementation of tasks that are inappropriate in views. |

Let's finish with some overall recommendations for using JSP. The following guidelines may seem overly restrictive. However, the chances are that if you can't see how a JSP could work within them, it is probably trying to do inappropriate work and needs to be refactored.

Uses JSP pages purely as views. If a JSP does something that couldn't be accomplished by another view technology (because of the integration with Java or the sophisticated scripting involved) the app's design is at fault. The code should be refactored into a controller or business object.

<%@ page session="false" %>

This will improve performance, and enforces good design practice. Views shouldn't be given access to session data, as they might modify it, subverting good design. It's the job of controllers, not views, to decide whether a user should have server-side state in an HttpSession object.

This tutorial is about what you can use right now to build real apps. However, when major changes are signaled well in advance, there can be implications for design strategy. JSP 2.0 - in proposed final draft at the time of writing - will bring major changes to JSP authoring. In particular, it integrates the Expression Language introduced in the JSTL into the JSP core, simplifies the authoring of custom tags and adds a more sophisticated inclusion mechanism based on JSP fragments.

| Important |

JSP 2.0 will bring the most major changes in the history of JSP, although it will be backward compatible. Many of these changes tend to formalize the move away from Java scriptlets that most experienced Java web developers have already made. JSP 2.0 will bring the JSTL Expression Language into the JSP core, allowing easier and more sophisticated navigation of JavaBean properties. It will also allow for simpler custom tag definitions, without the need for Java programming. By avoiding scriptlets and learning to maximize use of the JSTL it's possible to move towards the JSP 2.0 model even with JSP 1.2. |

The only code we need to write as part of our app is the JSP exposing our model. However, first we'll need to create a view definition enabling the framework's view resolver to resolve the "Show Reservation" view name to our JSP view. The com.interface21.web.servlet.view.InternalResourceView class provides a standard framework implementation of the View interface that can be used for views wrapping JSP pages or static web app content. This class, discussed in Appendix A, exposes all the entries in the model Map returned by the controller as request attributes, making them available to the target JSP as beans with request scope. The request attribute name in each case is the same as Map key. Once all attributes are set, the InternalResourceView class uses a Servlet API RequestDispatcher to forward to the JSP specified as a bean property. The only bean property we need to set for the InternalResourceView implementation is url: the URL of the JSP within the WAR. The following two lines in the /WEB-INF/classes/views.properties file define the view named showReservation that we've taken as our example:

showReservation.class=com.interface21.web.servlet.view.InternalResourceView showReservation.url=/showReservation.jsp

This completely decouples controller from JSP view; when selecting the "Show Reservation" view, the TicketController class doesn't know whether this view is rendered by showReservation.jsp, /WEB-INF/jsp/booking/reservation.jsp, an XSLT stylesheet or a class that generates PDF. Let's now move onto actual JSP code, and look at implementing a JSP view for the example. We won't need to write any more Java code; the framework has taken care of routing the request to the new JSP. We'll do this in two steps: first implement a JSP that uses scriptlets to present the dynamic content; then implement a JSP that uses the JSTL to simplify things. These two JSP pages can be found in the sample app's WAR named showReservationNoSt1.jsp and showReservation.jsp respectively. In each case, we begin by switching off automatic session creation. We don't want a JSP view to create a session if none exists - session management is a controller responsibility:

<%@ page session="false" %>

Next we make the three model beans available to the remainder of the page:

<jsp:useBean type="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.referencedata.Performance" scope="request" /> <jsp:useBean type="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.referencedata.PriceBand" scope="request" /> <jsp:useBean type="com.wrox.expertj2ee.ticket.boxoffice.Reservation" scope="request" />

Note that as recommended above, I've specified the type, not class, for each bean, and each is given request scope. Now let's look at outputting the data using scriptlets, to demonstrate the problems that will result. The first challenge is to format the date and currency for the user's locale. If we simply output the when property of the performance, we'll get the default toString() value, which is not user-friendly. Thus we need to use a scriptlet to format the date and time parts of the performance date in an appropriate format. We use the java.text.SimpleDateFormat class to apply a pattern intelligible in all locales, ensuring that month and day text appears in the user's language and avoiding problems with the US and British date formatting convention - mm/dd/yy and dd/mm/yy respectively. We'll save the formatted text in a scripting variable, so we don't need to interrupt content rendering later:

<%

java.text.SimpleDateFormat df = new java.text.SimpleDateFormat();

df.applyPattern("EEEE MMMM dd, yyyy");

String formattedDate = df.format(performance.getWhen());

df.applyPattern("h:mm a");

String formattedTime = df.format(performance.getWhen());

%>

We need a similar scriptlet to handle the two currency values, the total price and tutorialing fee. This will use the java.text.NumberFormat class to obtain and use a currency formatter, which will prepend the appropriate currency symbol:

<% java.text.NumberFormat cf = java.text.NumberFormat.getCurrencyInstance(); String formattedTotalPrice = cf.format(reservation.getTotalPrice()); String formattedBookingFee = cf.format(reservation.getQuoteRequest().getBookingFee()); %>

Now we can output the header:

<b><%=performance.getShow().getName()%>:<%=formattedDate%> at <%=formattedTime%> </b> <br> <p> <%= reservation.getSeats().length %> seats in <%=priceband.getDescription()%> have been reserved for you for <jsp:getProperty property="minutesReservationWillBeValid"/> minutes to give you time to complete your purchase.

Since the <jsp:getProperty> standard action can't handled nested properties, I've had to use an expression to get the name of the show, which involves two path steps from the Performance bean. I also had to use an expression, rather than <jsp:getProperty>, to get the PriceBand object's description property, which is inherited from the SeatType interface. The Jasper JSP engine used by JBoss/Jetty 3.0.0 has problems understanding inherited properties - a serious bug in this implementation of JSP, which is used by several web containers. Now we need to iterate over the Seat objects in the seats array exposed by the Reservation object:

The seat numbers are:

<ul>

<% for (int i = 0; i < reservation.getSeats().length; i++) { %>

<li><%= reservation.getSeats()[i].getName()%>

<% } %>

</ul>

This is quite verbose, as we need to declare a scripting variable for each seat or invoke the getSeats() method before specifying an array index when outputting the name of each seat. Since we declared the formattedTotalPrice and formattedBookingFee variables in the scriptlet that handled date formatting, it's easy to output this information using expressions:

The total cost of these tickets will be <%=formattedTotalPrice%>. This includes a tutorialing fee of <%=formattedBookingFee%>.

A simple scriptlet enables us to display the link to allow the user to select another performance if the Reservation object indicates that the allocated seats were not adjacent. This isn't much of a problem for readability, but we do need to remember to close the compound statement for the conditional:

<% if (!reservation.getSeatsAreAdjacent()) { %>

<b>Please note that due to lack of availability, some of the

seats offered are not adjacent</b>

<form method="GET" action="payment.html">

<input type="submit" value="Try another date"</input>

</form>

<% } %

We can work out the seating plan image URL within the WAR from the show ID.

| Note |

There is one image for each seating plan in the /static/seatingplans directory, the filename being of the form <seatingplanId>.jpg. Note that building this URL in the view is legitimate; it's no concern of the model that we need to display a seating plan image, or how we should locate the image file. We'll include static content from this directly whichever view technology we use. |

We can use a scriptlet to save this URL in a variable before using the HTML <img> tag. This two-step process makes the JSP more readable:

<% String seatingPlanImage = "static/seatingplans/" + performance.getShow().getSeatingPlanId() + ".jpg"; %> <img src="<%=seatingplanimage%>" />

This version of the JSP, using scriptlets, isn't disastrous. The use of the MVC pattern has ensured that the JSP has purely presentational responsibilities, and is pretty simple. However, the complete page is inelegant and wouldn't prove very easy for markup authors without Java knowledge to maintain. Let's now look at using the JSTL to improve things. The following version of this page is that actually used in the sample app. Our main aims will be to simplify date and currency formatting and to address the problem of the verbose iteration over the array of seats. We will also benefit from the JSTL's Expression Language to make property navigation more intuitive where nested properties are concerned. We will begin with exactly the same page directive to switch off automatic session creation, and the same three <jsp:useBean> actions. However, we will need to import the core JSTL tag library and the formatting library before we can use them as follows:

<%@ taglib prefix="c" uri="htt://java.oracle.com/jst/core"%> <%@ taglib prefix="fmt" uri="htt://java.oracle.com/jst/core"%>

I'll start the listing where things differ. We can use the <c:out> tag and the JSTL expression language to output the value of nested properties intuitively. Note that now that we don't need to use scriptlets, we don't need the get prefix when accessing properties or the parentheses, making things much neater, especially where nested properties are concerned:

<b><c:out value="${performance.show.name}"/:>

As the above fragment illustrates, the Expression Language can only be used in attributes of JSTL tags, and expression language values are enclosed as follows: ${expression}. The use of special surrounding characters allows expressions to be used as a part of an attribute value that also contains literal string content. The JSTL expression language supports arithmetic and logical operators, as well as nested property navigation. The above example shows how nested property navigation is achieved using the . operator. Date formatting is also a lot nicer. We use the same patterns, defined in java.text.SimpleDateFormat, but we can achieve the formatting without any Java code, using the format tag library:

<fmt:formatDate value="${performance.when}" type="date" pattern="EEEE MMMM dd,

yyyy" />

at

<fmt:formatDate value="${performance.when}" type="time" pattern="h:mm a" />

</b>

<br/>

<p>

The JSTL doesn't allow method invocations through the expression language, so I had to use an ordinary JSP expression to display the length of the seats array in the reservation object (an array's length isn't a bean property):

<%= reservation.getSeats().length %>

seats in

<c:out value="${priceband.description}"/>

have been reserved

for you for

<c:out value="${reservation.minutesReservationWillBeValid}"/>

minutes to give you time to complete your purchase.

Iterating over the array of seats is much less verbose using JSTL iteration, because it enables us to create a variable, which we've called seat, for each array element. Things are also simplified by simple nested property navigation:

<c:forEach var="seat" items="${reservation.seats}">

<li><c:out value="${seat.name}"/>

</c:forEach>.

Currency formatting is also a lot nicer with the JSTL formatting tag library. Again, there's no need to escape into Java, and nested property access is simple and intuitive:

The total cost of these tickets will be

<fmt:formatNumber value="${reservation.totalPrice}" type="currency"/>.

This includes a tutorialing fee of

<fmt:formatNumber value="${reservation.quoteRequest.bookingFee}"

type="currency"/>.

For consistency, we use the JSTL core library's conditional tag, rather than a scriptlet to display the additional content to be displayed if the seats are not adjacent. Using markup instead of a scriptlet isn't necessarily more intuitive for a conditional, but again the Expression Language simplifies nested property access:

<c:if test="${!reservation.seatsAreAdjacent}">

<b>Please note that due to lack of availability, some of the

seats offered are not adjacent.</b>

<form method="GET" action="payment.html">

<input type="submit" value="Try another date"></input>

</form>

</c:if>

Finally, we use a nested property expression to find the URL of the seating plan image. Note that only part of the value attribute is evaluated as an expression - the remainder is literal String content:

<img src="

<c:out value="static/seatingplans/${performance.show.seatingPlanId}.jpg"/>"

/>

The two versions of this page use the same nominal technology (JSP) but are very different. The second version is simpler and easier to maintain. The example demonstrates both that JSTL is an essential part of the JSP developer's armory and that the JSTL completely changes how JSP pages display data. A JSP 2.0 version of this page would be much closer to the second, JSTL version, than the standard JSP 1.2 version shown first.

JSP is the view technology defined in the J2EE specifications. It offers good performance and a reasonably intuitive scripting model. However, JSP must be used with caution. Unless strict coding standards are applied, the power of J2EE can prove a grave danger to maintainability. The JSP Standard Template Library can make JSP pages simpler and more elegant, through its simple, intuitive Expression Language, and by supporting many common requirements through standard custom tags.

| Important |

Don't use just standard JSP. Use JSP with the JSTL. As our example illustrates, using the JSTL can greatly simplify JSP pages and help us to avoid the need to use scriptlets. |